The Comfort in a Bowl: A Deep Dive into New England Clam Chowder

The history of American gastronomy is a rich tapestry, but few dishes hold a place as warm, revered, and culturally significant as New England Clam Chowder. More than just a soup, this creamy, hearty preparation is an edible icon, a staple of coastal dining, and a culinary symbol of the region from which it hails. To stir a ladle through its thick, ivory broth, speckled with chopped clams, chunks of potato, and bits of smoky salt pork, is to partake in centuries of maritime tradition and culinary evolution.

A Dish Born of Necessity and the Sea

The very word “chowder” likely descends from the French term chaudron, meaning cauldron or large kettle, suggesting its origins as a simple, communal, one-pot meal. As early European settlers and fishermen arrived on the shores of New England, they brought with them the tradition of stewing fresh catch with available vegetables and hard biscuits to feed a crew. The abundant bounty of the Atlantic—particularly the hardshell quahog or surf clam—quickly became the foundational ingredient.

The earliest chowders were thinner, often milk-free, and relied on seawater, onion, and sea biscuits for texture and flavor. The addition of cream or milk, which is the defining characteristic of the modern New England style, was a later, crucial development. This transformation elevated the dish from humble ship fare to a creamy, luxurious preparation fit for any table. By the 18th century, clam chowder was a recognized and popular meal in the colonies, with recipes appearing in the first American cookbooks. The enduring appeal lies in its simplicity: it’s a direct reflection of the land and the sea, utilizing just a few core ingredients to achieve profound comfort.

Anatomy of the Perfect Chowder

While nearly every seafood restaurant and home cook in New England claims to have the definitive recipe, the authentic style adheres to an unwritten constitution of ingredients and preparation. The distinctiveness of the New England style, sometimes referred to as Boston Clam Chowder, is its milk or cream base. This distinguishes it sharply from its rival, the tomato-based Manhattan Clam Chowder.

The Core Components:

- Clams: The soul of the dish. Most commercial recipes use canned or frozen minced clams for consistency and texture, but the very best chowders use freshly shucked quahogs. The clam liquor, the briny liquid released during shucking or contained within the can, is absolutely essential, providing the deep, oceanic base flavor.

- Salt Pork or Bacon: This is the flavor starter. Small cubes of salt pork or good quality bacon are slowly rendered in the pot to create the fat that will cook the vegetables. This step introduces a critical layer of smokiness and saltiness that balances the sweetness of the cream and the earthiness of the potato.

- Dairy: Heavy cream, light cream, or whole milk is used to create the signature velvety texture and rich, white color. The choice of dairy determines the richness of the final product.

- Vegetables: Almost universally, this means potatoes (usually a waxy variety like Yukon Gold, which holds its shape) and onions. Some recipes may include a bit of celery, but purists argue this is unnecessary.

- Thickening Agent: The thickness comes from either adding a roux (butter and flour) or by allowing the starch from the chopped potatoes to naturally thicken the liquid during simmering. A proper New England Clam Chowder should be thick enough to coat a spoon, but not so dense that it resembles pudding.

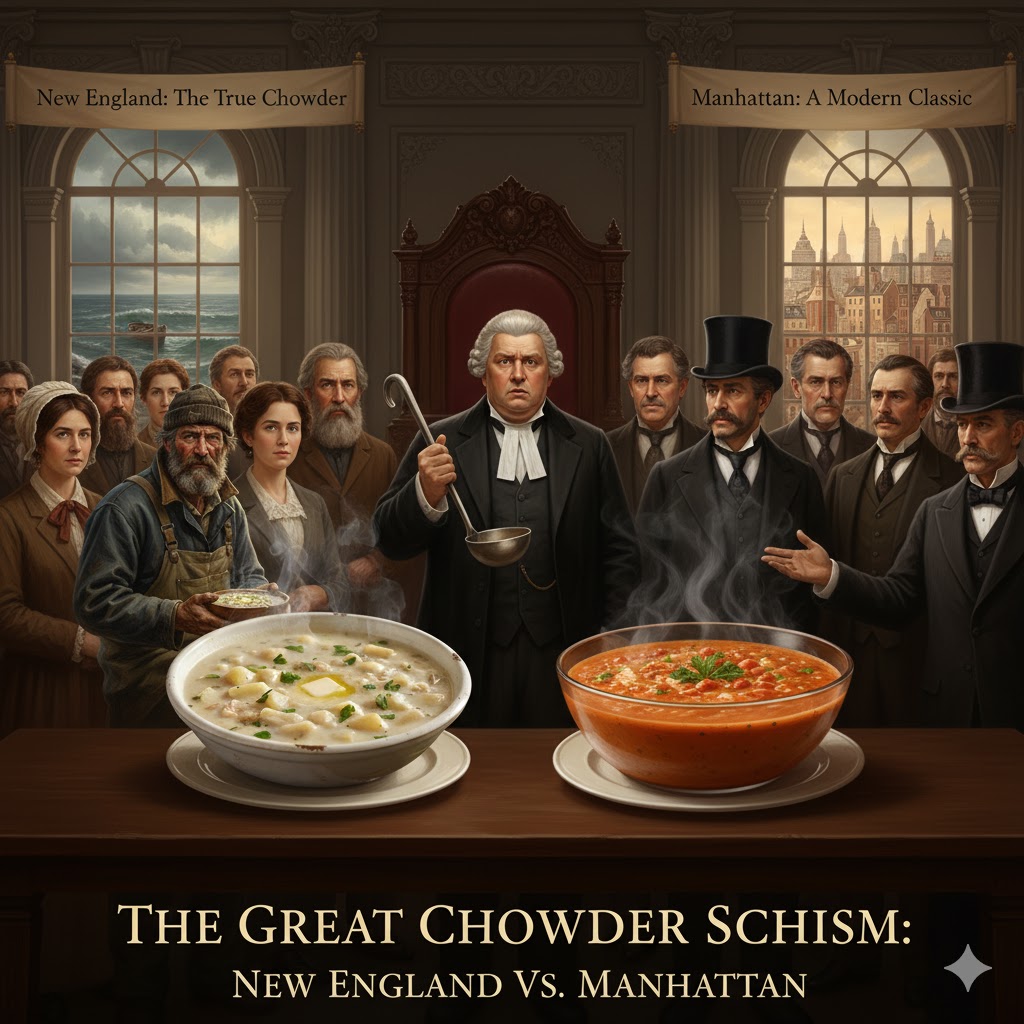

The Great Chowder Schism: New England vs. Manhattan

No discussion of clam chowder is complete without acknowledging the infamous rivalry, a culinary cold war that pits the creamy New England style against the reddish-hued Manhattan Clam Chowder.

The Manhattan version, which relies on a tomato base (a late 19th-century addition, possibly influenced by Italian and Portuguese immigrant cooking) instead of cream, is considered an abomination by many New Englanders. The debate is often heated, with New Englanders firmly believing that the inclusion of tomato dilutes the authentic clam flavor.

The intensity of this regional divide was immortalized in 1939 when a Maine state legislator attempted to introduce a bill that would have made the use of tomatoes in clam chowder illegal. While the legislation failed, the sentiment it represented persists: for a New Englander, the chowder must be white. The simple truth is that while the Manhattan style is a perfectly valid and delicious soup, the term “clam chowder” for most Americans first and foremost evokes the creamy, quintessential New England version.

The Art of the Serve

Serving New England Clam Chowder is as much a part of the tradition as the cooking itself. It is almost always accompanied by oyster crackers—small, hexagonal, dry crackers—which are often crushed and sprinkled over the top just before eating. A side of crusty, unsalted bread for dipping and soaking up the last bits of the rich broth is also customary.

In coastal towns, particularly around Cape Cod, it is often served in a bread bowl—a hollowed-out, round loaf of sour bread—which makes a dramatic and delicious vessel that can be eaten once the soup is finished.

The perfect chowder is not only a feast for the palate but a sensory experience that tells the story of the sea. The briny perfume rising from the bowl, the creamy-white color, the smoky depth from the pork, and the comforting chew of the clam and potato all contribute to a dish that is deeply satisfying. It is the perfect antidote to a chilly day, a celebratory meal after a successful day on the water, or a quiet reminder of coastal life.

A Timeless Legacy

New England Clam Chowder’s enduring legacy is a testament to the power of simple, honest cooking. In an era of elaborate and deconstructed cuisine, the chowder remains unchanged and unpretentious. It is a culinary benchmark—the first thing tourists seek out and the last thing natives crave when they are away from home.

The dish has traveled far beyond the rocky coastline of Massachusetts and Maine, finding its way onto menus across the globe. Yet, to truly appreciate its character, one must savor it where it began: overlooking the cold, gray Atlantic, with the smell of salt in the air. Here, in its native environment, the New England Clam Chowder is more than a recipe; it is a warm, liquid embrace of American maritime history and the quintessential comfort food of the Northeast.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) about New England Clam Chowder

Q1: What is the main difference between New England Clam Chowder and Manhattan Clam Chowder? A: The main difference is the base. New England Clam Chowder (often called Boston Clam Chowder) uses a milk or cream base and is thick and white. Manhattan Clam Chowder uses a tomato base (and often contains other vegetables like carrots and celery) and is thinner and red/orange.

Q2: What are the essential ingredients in an authentic New England Clam Chowder? A: The essential ingredients are:

- Clams (usually hard-shell quahogs or surf clams) and clam liquor.

- Salt pork or bacon (for the essential smoky/salty flavor base).

- Potatoes (waxy varieties like Yukon Gold are best).

- Onions.

- Cream or milk (heavy cream is often preferred for richness).

Q3: Why is New England Clam Chowder so thick? A: The thickness comes from two main sources:

- A roux (a cooked mixture of butter and flour) added to the base.

- The starch released from the chopped potatoes as they simmer in the broth. The chowder should be thick enough to coat a spoon, but not overly pasty.

Q4: Can I use fresh clams, canned clams, or frozen clams? A: You can use all three. Freshly shucked clams are considered the best for flavor, but good quality canned minced clams are used by most professional and home cooks for convenience and consistency. If using canned, always save the clam liquor (the juice in the can) as it is essential for the authentic briny flavor.

Q5: What are “oyster crackers” and why are they served with the chowder? A: Oyster crackers are small, unsalted, dry crackers that are traditionally served alongside clam chowder (and other creamy soups). They are typically crushed and sprinkled over the top of the chowder just before eating, adding a bit of salty crunch and texture contrast.

Q6: What is the best way to reheat leftover clam chowder? A: Chowder is best reheated gently on the stovetop over low to medium-low heat. Constant stirring is important to prevent the cream from scalding or the potatoes/clams from sticking to the bottom of the pot. Avoid boiling the chowder.

Q7: Where did the name “chowder” come from? A: The word “chowder” is believed to be derived from the French word “chaudron,” meaning “cauldron” or “large kettle.” This reflects the dish’s origins as a simple, communal, one-pot meal cooked by early European settlers and fishermen.

Leave a Reply